Nguyen Minh (c) REUTERS

Nguyen Minh (c) REUTERSSoutheast Asia’s military modernization over the last half decade has been impressive. Defense expenditures across the region have risen, on average, by nine percent each year since 2009, but the region’s countries have not been uniform in their approaches. The degree to which those countries with maritime interests have modernized their militaries appears to be increasingly linked to their strategic concerns related to changes in the geopolitical environment, edging out domestic considerations that have long dominated many of their military procurement decisions. In this “Topics of the Month,” I compare the approaches of various states in the region and raise questions about the sources of differences, which may stimulate an exchange of opinions.

Of course, the biggest change in Southeast Asia’s geopolitical landscape has been the rise of China. In the years immediately after the Cold War, it seemed to be a net positive for regional stability. China improved relations with many neighbors by resolving or downplaying territorial disputes. It reassured them with pledges of heping jueqi (peaceful rise) and hexie shijie (harmonious world). In 2002, Beijing’s willingness to sign the ASEAN’s “Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea” (code of conduct) raised hopes. The code sought to reduce the risk of conflict over the islands and waters of the South China Sea, whose sovereignty is contested. Though it had no enforcement mechanism, most Southeast Asian countries saw it as a stepping stone to China’s acceptance of a multilateral resolution of the issue.

Later efforts to turn the code into a binding agreement stalled. China insisted on bilateral negotiations with individual disputants. Meanwhile, China’s fast-growing economy allowed it to pursue even faster military modernization, which created the ability to project power deep into the South China Sea. In 2007, China began to take a more assertive stance on its “nine-dashed line” claim It raised the status of the administrative authority responsible for the Paracel (Xisha) and Spratly (Nansha) Islands to that of dishiji (prefectural-level city) in Hainan Province, then it.began to list its South China Sea claims among its “core interests”—those over which it was willing to fight.

Sensing the start of a slippery slope, Southeast Asian countries with a direct stake in the South China Sea dispute confronted China at the seventeenth ARF in 2010. China was furious and, according to the Philippines and Vietnam, increased its harassment of their fishing and oil exploration ships in the disputed waters. Tensions rose again when China built structures near Philippine-claimed Amy Douglas Bank and escalated when its ships blocked Philippine access to Scarborough Shoal in 2012 at a time when China and Japan were tussling over the sovereignty of the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands. By the end of 2013, China had declared an air defense identification zone over much of that sea, raising concerns in Southeast Asia that it might do the same over the South China Sea.

Sensing the start of a slippery slope, Southeast Asian countries with a direct stake in the South China Sea dispute confronted China at the seventeenth ARF in 2010. China was furious and, according to the Philippines and Vietnam, increased its harassment of their fishing and oil exploration ships in the disputed waters. Tensions rose again when China built structures near Philippine-claimed Amy Douglas Bank and escalated when its ships blocked Philippine access to Scarborough Shoal in 2012 at a time when China and Japan were tussling over the sovereignty of the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands. By the end of 2013, China had declared an air defense identification zone over much of that sea, raising concerns in Southeast Asia that it might do the same over the South China Sea.More immediate concerns arose in 2014. Chinese offshore oil drilling near the Paracel Islands sparked a bitter row with Vietnam. Then, the Philippines revealed images of Chinese land reclamation activities on Johnson South Reef. Soon after, Chinese construction was spotted on several other disputed islands. Among the latest was the expansion of a harbor and runway on Woody Island in the Paracel group and dredging near Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly group. China also rebuffed Southeast Asian attempts at the twenty-first ARF in August 2014 to implement a voluntary freeze on actions that could aggravate territorial disputes in the South China Sea were rebuffed. As the deputy head of the Foreign Ministry’s Boundary and Ocean Affairs Departments explained, “The Spratly Islands are China’s intrinsic territory, and what China does or doesn’t do is up to the Chinese government.”6

Over the same period, doubts in Southeast Asia about American commitment to the region have grown. Those doubts had bubbled up soon after the Cold War ended, but after the United States became entangled in Afghanistan and Iraq, they gained new currency. Many see a war-weary United States as increasingly reluctant to act, despite its much-talked-about “rebalance” to Asia and recent interjection into the South China Sea dispute—an impression reinforced by cuts in the US defense budget even as China has continued its military buildup.

How Southeast Asia’s countries have viewed these geopolitical changes can be seen in the scope and speed with which they have pursued their military modernizations. The Philippines and Vietnam, which have been most exposed to the sharp end of China’s assertiveness, have attempted the broadest and fastest military modernizations. Others, like Indonesia and Malaysia, have selectively modernized to hedge the new geopolitical uncertainties in the region.

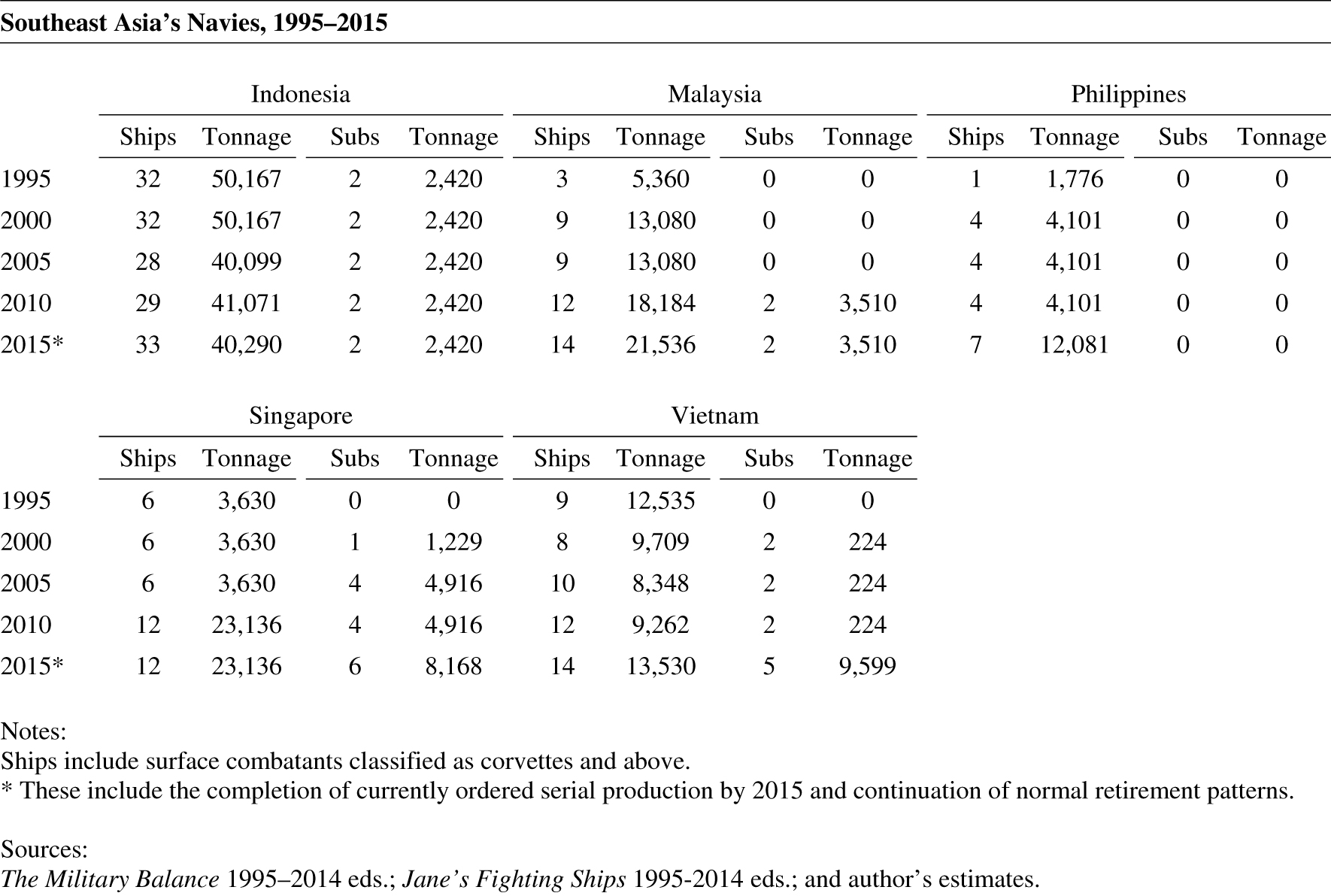

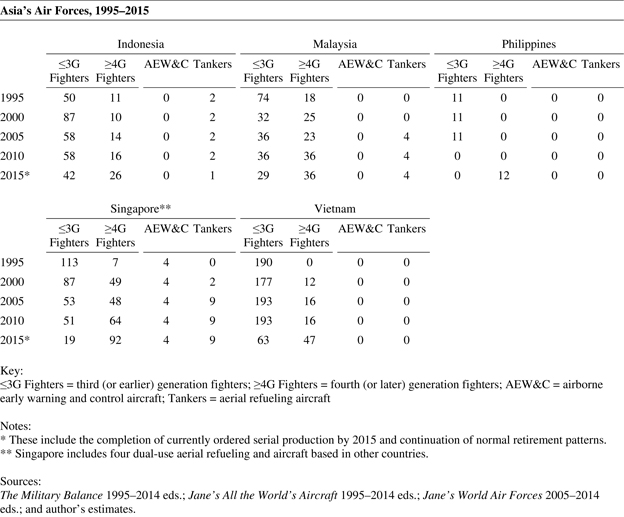

The differences are made even clearer by the sort of contingencies that the region’s military modernizations are designed to meet. Since the specks of contested terrain in the South China Sea are far less strategically important than the seas around and skies above them, countries concerned about those waters have devoted more resources to modernizing their naval and air forces. Given that such forces largely rely on combat platforms to generate their combat capabilities, we can use them to trace the trace the trends in their military modernizations.

The differences are made even clearer by the sort of contingencies that the region’s military modernizations are designed to meet. Since the specks of contested terrain in the South China Sea are far less strategically important than the seas around and skies above them, countries concerned about those waters have devoted more resources to modernizing their naval and air forces. Given that such forces largely rely on combat platforms to generate their combat capabilities, we can use them to trace the trace the trends in their military modernizations.Philippines

The sense of urgency in the Philippines’ military modernization is palpable. Manila has realized that it must create what President Benigno Aquino III calls “a minimum credible deterrent” if it is to stand a chance of holding onto its South China Sea claims. Since its independence, the Philippines has relied on a mutual defense treaty with the United States to guarantee its territorial defense, but that treaty fails to spell out whether the United States would help defend claims in the South China Sea if they are disputed. While that may keep China guessing, it forces the Philippines to periodically check its read on America’s commitment. Currently, it senses that the United States might equivocate. Hence, it was keen to sign the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement in April 2014, not only to bind the United States a little closer, but also to buy itself time to rebuild its territorial defense forces. For decades, the Philippines let those forces wither, focusing its military resources on internal security to fight a series of long-lived communist and Muslim insurgencies. That problem was compounded in 1991 when the Philippine Senate rejected a treaty that would have extended the lease on American military bases in the country. While that may have satisfied popular opinion at the time, its navy could no longer rely on US military assistance credits to buy ships or spare parts; and its air force could no longer access American logistics and maintenance support at Clark Air Base.

After US forces left the Philippines, China occupied Philippine-claimed Mischief Reef in 1995. In response, the Philippine Congress passed the Armed Forces of the Philippines Modernization Act to transform the Philippine military into one capable of territorial defense. But the funding never materialized. Apart from the purchase of four Peacock-class corvettes from the United Kingdom, the Philippines made no major naval or air acquisition for the next 13 years. Its navy came to lack all the basic equipment needed for modern warfare: anti-ship cruise missiles, anti-missile defenses, and integrated communications and sensors. The Philippine air force was no better off. It retired its last jet fighter in 2005.

As late as 2010, few expected the Philippines to modernize its military in any meaningful way, but China’s renewed assertiveness in the South China Sea and the Philippines’ concurrent economic expansion changed that. In 2011, Manila approved $118 million in supplemental funding to protect the Malampaya Natural Gas and Power Project, a critical part of the national energy infrastructure in the South China Sea. Then, Aquino signed legislation to invest $1.8 billion over five years into the modernization of the Philippine armed forces. In July 2014, he submitted a defense budget request for $2.6 billion, a nearly 30 percent increase over 2013.9 The funding enabled the navy and air force to begin restoring their capabilities. In 2011, Manila purchased two retired Hamilton-class coast guard cutters from the United States. It is currently deliberating over how best to use $355 million in allocated funds to furnish the two former cutters with new weapons, sensors, and engineering upgrades, and before the year’s end, South Korea is expected to transfer to the navy a retired Po Hang-class corvette, already outfitted with anti-ship missile launchers, as well as several smaller crafts. These gifts follow Manila’s $528 million-worth of deals to purchase a dozen FA-50 light attack aircraft and eight Bell 412 utility helicopters from South Korea.

Military modernization seems to have hit its stride in 2014. In February, Manila announced its intention to procure two new frigates at an estimated cost of $400 million, after it abandoned an earlier plan to buy two retired Maestrale-class frigates from Italy. In May, it issued a tender for six close-air-support aircraft worth $114 million and another for anti-submarine warfare helicopters worth $121 million. It also finished pre-negotiations with Israeli Aerospace Industries to acquire three surveillance radars in a deal worth $57 million. The following month, the Philippines issued another tender for two long-range maritime patrol aircraft worth $136 million, and in July, it signed a contract with Indonesia’s PT PAL to build two landing platform docks (LPD) for $92 million. In addition, the Philippines seems to want its new military hardware fast. It expects delivery of its LPDs within two years and its close-air-support and maritime patrol aircraft within 18 and 34 months after their respective contracts are signed.

Manila’s eagerness to rebuild its defense forces has sometimes exceeded its budgetary capacity. That was the case with its new naval base at Ulugan Bay on Palawan Island, near the Spratly Islands. It had hoped to “finance the [$11.4 million] upgrades, which include building piers for larger vessels and installing maritime surveillance radar systems, through the Philippines’ Malampaya Fund, which accumulates royalties from oil and gas operations in the waters off Palawan Island.” But the Philippine Supreme Court ruled that it could not use the fund’s money that way. Legislators had to revise the fund’s rules so that they would permit military expenditures related to the protection of the Malampaya natural gas field in the South China Sea.

Manila has taken an even bigger step to change the rules under its 2003 Government Procurement Reform Act, which had been originally designed to instill competition and transparency into government procurement. A bill approved in May 2014 by the Senate finance committee expanded the cases where Manila could approve without the need for public tendering procurements including: “aircraft, vessels, tanks, armored vehicles, high-tech communications equipment, radar systems, sophisticated weapon systems and high-powered firearms” from strategic allies. For the moment, that encompasses only the United States.

In the face of regular challenges from China in the South China Sea, Manila has raced to modernize its military. The Philippines has come farther and faster than many thought possible. But it has a long way to go. Fortunately for the Philippines, its diplomats have done a good job of applying pressure on China at a United Nations arbitration tribunal and at various ASEAN forums, putting China on the legal defensive and also earning new supporters among its neighbors and time to modernize.

Vietnam

Vietnam Unlike the Philippines, Vietnam managed to settle part of its maritime border dispute with China in 2000, despite the long history of conflict between the two. In 2011 and 2012, however, Chinese patrol boats cut the cables used by Vietnamese oil exploration ships to conduct seismic surveys in the South China Sea. The most recent flare up occurred in May 2014, when Hanoi contested Beijing’s use of an offshore oil drilling rig in disputed waters near the Paracel Islands. The confrontation led to Chinese and Vietnamese patrol boats ramming each other at sea and violent anti-Chinese protests in Vietnam. Hanoi even suggested that it may, like the Philippines, legally challenge China’s claims in the South China Sea at the United Nations.

While many Vietnamese may be ready to challenge China, Hanoi has been more careful, aware that Vietnam has lost every naval engagement it has had with China in recent memory. Modern naval warfare requires capable combat platforms, and Vietnam has few of these. Until the last decade, much of its navy and air force was still equipped with Soviet-era warships and combat aircraft. The navy’s five Petya-class frigates and eight Osa II-class fast attack craft and the air force’s 140-odd MiG-21 fighters and Su-22 attack aircraft are, essentially, obsolete. Vietnam’s only attempts to recapitalize its forces during the 1990s were the purchase of four Tarantul-class corvettes and 12 Su-27SK fighters. Until the mid-2000s not much had changed, apart from the addition of four Su-30MK2 fighters, two Svetlyak-class fast attack craft, and an order for ten Tarantul V-class corvettes (only two of which were ever confirmed to have been delivered).

Hanoi finally got serious about defending its South China Sea claims in 2007, when Vietnam’s communist party adopted a resolution to develop a national “Maritime Strategy Towards the Year 2020.” That was followed by a 2009 defense white paper, which underlined the resolve to protect maritime sovereignty and to pursue military modernization to do so. Vietnam began a rapid succession of military hardware acquisitions, reaching agreements with Russia to supply six Kilo-class diesel-electric attack submarines, four Gepard-class frigates, four more Svetlyak-class fast attack craft, and 20 Su-30MK3 fighters. In 2013, it ordered another batch of 12 Su-30MK2 fighters from Russia and four Sigma-class corvettes from a Dutch shipbuilder.

The contours of a defense strategy designed to protect Vietnam’s maritime claims began to emerge, taking full advantage of its long coastline’s proximity to (and China’s distance from) disputed areas. It has stationed its new submarines and combat aircraft in southern Vietnam, outside the unfueled combat range of Chinese land-based strike assets, but near the Paracel and Spratly Islands. In 2011, it acquired two batteries of Russian P-800 mobile land-based anti-ship cruise missiles (part of the K-300P Bastion-P coastal defense system) that can hit naval targets in the South China Sea from anywhere along its coast. Being mobile, the batteries would be difficult for China to locate and suppress. Vietnam has expressed interest in additional missile batteries.

It also plans to bolster its newly-consolidated coast guard. In 2013, it commissioned three retired South Korean patrol boats. This year, Hanoi announced that it would spend $547 million to build 32 new vessels for its coast guard and fisheries surveillance forces. Next year, Japan will deliver six refurbished Japanese coast guard cutters that are valued at $4.9 million. Vietnam also expects to receive financial assistance from Japan’s ODA program for several newly built offshore patrol vessels. To support newly acquired combat capabilities, Vietnam has started a concerted effort to remake its naval and air maintenance infrastructure. In 2006, it contracted with Russia to upgrade its venerable naval base at Cam Ranh Bay with new maintenance and repair facilities for ships and submarines. Its air force is training engineers and technicians in Russia to perform depot-level maintenance for a growing fleet of Su-30MK2 fighters at Bien Hoa Air Base.

Vietnam’s military modernization efforts over the half decade have been dramatic. The value of the orders for just its new Kilo-class submarines and Su-30MK2 fighters is almost $3 billion, roughly equivalent to its defense budget for 2014. According to Jane’s Defence Budget, “the navy’s budget has increased by 150 percent since 2008 to $276 million in 2011 and is expected to grow to $400 million by 2015.” In June 2014, Vietnam’s legislature endorsed a new $756 million plan to further boost the country’s maritime surveillance and defense capabilities.

Equally notable has been the pace of Vietnam’s military modernization. In June 2014, the keel of the sixth Kilo-class submarine that Vietnam ordered from Russia in 2009 was already being laid down. Some expect the last batch of Su-30MK2 will be delivered as early as 2015, only two years after they were ordered. To further speed its modernization, Vietnam replaced its 2005 military procurement rules in July 2014, circumventing the normal competitive process so that “urgent bidding packages [can] be carried out… to protect national sovereignty, national borders, and islands”.

Given the breadth and speed of its military modernization, Vietnam has quickly outstripped its ability to finance new purchases. To pay for the Russian arms that it ordered in 2009, it likely linked them to other deals of interest. That same year, Gazprom signed a lucrative agreement with PetroVietnam to jointly develop a number of Vietnam’s offshore natural gas fields in the South China Sea. A second deal between Rosatom and Vietnam’s largest utility was struck to build Vietnam’s first nuclear power plant, valued at about $8 billion.

While its military modernization has been costly, Vietnam may have felt it had little choice after witnessing China’s recent behavior in the South China Sea. It has reached out to any major power that might help: Russia, India, Japan, and even the United States. As Lieutenant General Nguyen Chi Vinh, Vietnam’s Deputy Minister of National Defence, said: “In the past, Vietnam used to cooperate in national defense with socialist… countries. Now we must follow the Party’s open policy by cooperating with many countries [all] over the world”.

Malaysia

Malaysia has been a long-time champion of international cooperation, particularly within Southeast Asia. Considering major power rivalries in the region as the biggest threat to its security, Malaysia has long urged its neighbors to band together. It was one of the drivers behind the creation of ASEAN in 1967. From Malaysia’s perspective, it is more preferable to balance the interaction of external powers with the whole region, than let them create their own balance within it. Ironically then, Malaysia has not rallied behind the Philippines and Vietnam to resist China’s new assertiveness. Like its fellow ASEAN countries, Malaysia has territorial claims in the South China Sea that conflict with those of China, but it has kept a low profile. Rather than confront Beijing, Malaysia has sought to capitalize on China’s economic growth.

By the second half of the 2000s, it began to have second thoughts. In 2007, Malaysia established a new naval base at Sepanggar Bay, next to the South China Sea, where it planned to station its two Scorpene-class diesel-electric attack submarines, but what really made it worry was when four Chinese warships conducted an amphibious exercise near Malaysia-claimed James Shoal in March 2013. It bristled with a rare official protest to Beijing; then it announced that it would create a marine corps and build a naval base at Bintulu, near the disputed shoal. China was unmoved. In February 2014, its navy held a second exercise off the same shoal. Malaysia officially shrugged it off, but one government advisor observed that the Chinese exercises off James Shoal were “a wake-up call that it could happen to us and it is happening to us… James Shoal has shown to us over and again that when it comes to China protecting its sovereignty and national interest it’s a different ball game”.

To play that game, more of the burden of maritime security will fall on the Malaysian navy, which currently consists of two submarines and 14 frigates and corvettes. On order are six Gowind-class corvettes, designed to operate in the littoral waters of the South China Sea and likely to be equipped with medium-range surface-to-air missile defenses, a much-needed addition to the fleet. However, expansion of the shipyard has taken precedence over construction on the first ship, which is not expected to enter the water until 2018. Even after all the new corvettes are commissioned, the navy would still be hard pressed to secure the country’s vast territorial waters. In 2013, Malaysia’s navy chief stated that he would need six or seven ships simultaneously on patrol to provide adequate maritime security, implying a minimum force of well over twenty ships.

Malaysia’s air force is in a similar state. Though it includes a good proportion of fourth-generation combat aircraft, many of them, particularly its MiG-29N fighters, are no longer operational. During the mid-1990s, Malaysia procured 16 MiG-29N fighters from Russia and eight F/A-18D fighters from the United States, but maintaining separate logistics systems for the two types of aircraft has reduced operational readiness and the ability to deploy either one away from its home base for long. That makes it tough for the air force to support naval units in the South China Sea. Malaysia’s purchase of 18 Su-30MKM fighters does little to solve these underlying problems. In any case, the air force believes that it needs a minimum of six full-strength combat squadrons to properly cover both halves of Malaysia, rather than the four of varying strength that it has.

Malaysian officials may have begun to recognize the need for a more determined military modernization in light of China’s actions in the South China Sea, but budgetary pressures and lingering ambivalence towards confronting China have restrained the pace of acquisitions. The Sulu raid on Sabah in March 2014 further diverted Malaysian attention from strengthening its naval and air forces. Military modernization has, thus, continued much as it always has. The Malaysian navy’s first Scorpene-class submarine took seven years to build before it was commissioned in 2009. That, it seems, will also be the case for the navy’s new Gowind-class corvettes. (In contrast, Vietnam’s first Kilo-class submarine took half the time to bring into service.) More worrisome, Malaysia appears to have put on hold its air force’s long-time requirements for airborne early warning and control aircraft and for a multi-role combat aircraft to replace its inoperable MiG-29N fighters.

Malaysia still conducts military exercises in the South China Sea to show its resolve, as it did in September 2014, when it touted that its Su-30MKM fighters launched Kh-31 anti-radiation missiles for the first time. But its military modernization efforts have been lackluster. They have seemed more concerned with simply recapitalizing its existing forces, rather than building them up. There is only so long Malaysia can delay a more robust modernization before it invites more Chinese forays. Fortunately for it, the reasons that underpin its long-standing preference for strong ties with China have begun to wane.

Indonesia

Spread across thousands of islands, Indonesia has had a number of maritime disputes with its neighbors. But since its konfrontasi with Malaysia in the 1960s, it has generally found peaceful ways of managing them. In 2003, it reached an agreement with Vietnam over their continental shelf boundary. In May 2014, it settled another dispute with the Philippines over the boundary between their exclusive economic zones (EEZ) in the Mindanao and Celebes Seas. Yet, the dispute with China has proven to be more challenging. So far, it has kept its distance from the territorial frays over the Paracel and Spratly Islands, at times even trying to play the role of mediator between the disputants; but it has always been one of them. As an archipelagic state, Indonesia is entitled to an EEZ around its Natuna Islands in the South China Sea, within which lie some of Indonesia’s largest offshore natural gas fields. Unfortunately, part of its EEZ also falls inside China’s claim line. For decades, Chinese naval and air forces have lacked the ability to enforce China’s maritime claims; so, Indonesia could minimize its dispute and focus on forging economic ties. It has been fearful that even the admission of a dispute would lend credence to China’s claim; but that era is ending. When the Chinese navy held its drills off Malaysia-claimed James Shoal, only 250 kilometers from Indonesian waters, Jakarta took notice.

In 2010, Indonesia submitted a letter to the United Nations’ Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to contest China’s claim on the South China Sea. Then, in a show of force, it conducted a major military exercise, called Angkasa Yudha, on Natuna Island in October 2013. But neither deterred Beijing, which in early 2014 unveiled a new official map interpreted as hardening claims over the South China Sea. In response, the Indonesian military announced preparations to strengthen its defenses of the Natuna Islands. The army would station a new infantry battalion there; the navy would improve naval facilities at Pontianak on nearby Borneo; and the air force would build new hangars and extend a runway at Ranai Air Base on Natuna Island to accommodate a new fighter squadron. General Moeldoko, chief of the Indonesian armed forces, expressed dismay over China’s map and his determination to defend the Natuna Islands.

With what forces Indonesia would defend its maritime claims is less clear. The closest it has come to describing how it would match resources with mission requirements was its 2010 Strategic Defense Plan, which promised to form a “Minimum Essential Force” to defend the country from external threats. That force envisioned a navy organized into a “Striking Force” of 110 ships, a “Patrolling Force” of 66 ships, and a “Supporting Force” of 98 ships, and an air force organized into ten fighter squadrons with 180 fighters. The plan offered insight into what the Indonesia’s navy and air force believe is needed for the country’s external defense. At the moment, the navy is hamstrung by not only an insufficient number of ships, but also insufficient resources to maintain those that it already has. It can currently put to sea two submarines, six frigates, 22 corvettes, and 12 fast attack craft, but many of its six Van Speijk-class frigates and 15 Parchim I-class corvettes already suffer from chronic maintenance problems. Most of the fleet’s hulls are over 30 years old. Today, submarines are among the highest priorities for the navy. It hopes to procure a dozen. In 2011, it awarded a South Korean shipbuilder a contract for three Type 209/1400 diesel-electric attack submarines. The navy also ordered two Sigma-class corvettes, which are intended to provide greater air defense, and has begun commissioning ships from two new classes of fast attack craft. However, some question whether Indonesia will be able to maintain the size of its fleet, given the rate at which its older ships are nearing the end of their service lives. Keeping so many aging ships in service will grow ever more burdensome, particularly because their systems vary so widely across origin and time.

The Indonesian air force has struggled to maintain its capabilities. Most frontline fighters consist of a collection of A-4E, F-5E/F, F-16A/B, Su-27SK/SKM, and Su-30MK/MK2 that were acquired in small batches since the 1980s. Many are in barely serviceable condition, but in 2012, the air force began to rectify that situation when it acquired 24 retired F-16C/D fighters from the United States that will be equipped with new radar systems designed to enhance their maritime and strike capabilities. The first arrived at Roesmin Nurjadin Air Base in July 2014. Once all 24 are delivered, Indonesia plans to upgrade its ten older F-16A/Bs to the new standard. In the longer term, Indonesia has agreed to participate in South Korea’s KF-X program to develop a next-generation fighter, which is anticipated to enter service after 2020.

Military modernization efforts remain relatively modest. Even its ambitious 2010 Strategic Defense Plan is not slated to be complete until 2024. Ongoing efforts will only incrementally lift its combat capabilities, rather than propel them to new heights. Moreover, its biggest orders appear relatively unhurried. The navy has allowed the delivery date for its three Type 209/1400 submarines to slip until 2019. Its two Sigma-class frigates are not expected to be delivered until late this decade. According to one report, none of its previously announced military upgrades on the Natuna Islands has even been started. Thus, Indonesia’s military modernization may end up looking more like Malaysia’s than those of the Philippines and Vietnam.Conclusion The prominence of China in the strategic calculations of countries in Southeast Asia is undeniable. Even in the early 1990s, many had already begun to consider how China could change the region’s geopolitical environment. They held “the belief that China regards the region as an area of influence with which relations should be structured hierarchically,” with China at the top. They feared that “as a mosaic of different cultures and ethnic groups, Southeast Asia lacks the political unity to resist the natural and historical tendency of the Chinese to push southward.” Ironically, at that time, Indonesia and Malaysia were seen as the countries that would most likely be apprehensive about China’s rise, given their troubled relations with their ethnic Chinese minorities. And while those relations have remained uneasy, it is the Philippines and Vietnam that have become most concerned about China’s rise.

Indeed, the rise of China has also been a story about the changes in Asia’s political order. The United States has seen its regional primacy fade. Southeast Asian countries had hoped that they could head off any tensions that might accompany China’s rise by persuading it to adopt their multilateral way of thinking, but China never did. Instead, the growth of Chinese power has led to greater tensions. Still, those concerns are not yet quite as dire as they are portrayed at times. They are tempered in many countries by the hope that they can continue to benefit from China’s economic growth and that, in time, Chinese behavior will moderate.

Just how concerned Southeast Asian countries have become about the changes in the region’s geopolitical landscape has been reflected in the scope and speed of their military modernization efforts, particularly of their naval and air forces. Worries over China’s territorial ambitions and America’s long-term commitment to the region have been catalysts for the Philippines and Vietnam to embark on their far-reaching and rapid military modernization programs, but the geopolitical environment is not static. Changes can still influence whether more Southeast Asian countries behave like the Philippines and Vietnam. The bellwether countries are Indonesia and Malaysia. While they are currently hedging their bets, they have edged closer to challenging China’s maritime ambitions than at any time in the past. Should their concerns intensify, one would expect to see them reflected in expansions of their military modernization efforts.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar

Catatan: Hanya anggota dari blog ini yang dapat mengirim komentar.