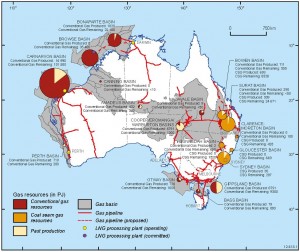

By Colin Clark  australia gas and oil map

australia gas and oil map

In World War II, this country served the allied cause as a giant aircraft carrier and port, providing planes, men and materiel to deploy throughout the Pacific. Allied aircraft flew from the northeastern town of Cairns during the Battle of the Coral Sea — known by some as the “battle that saved Australia.”

The Battle of Milne Bay on the eastern tip of New Guinea, little known to Americans, marked the first time allied troops turned back what had been the unstoppable Japanese. Australians fought that battle, aided by allied aircraft flying from an airstrip inland of the port of Townsville, which played crucial roles in virtually every battle of the Pacific.

Today, the strategic situation is very different. The greatest threats to peace in the region are North Korea and an increasingly assertive China. Indonesia has replaced Japan as the central threat faced by the Australia, although relations between the two states have improved considerably over the last two decades. Defense policymakers still consider the Aussie military’s ability to defeat Indonesia a primary benchmark.

What does all this translate into? Defend Australia from the north (hence the carefully circumscribed agreement to allow US Marines to operate from Darwin but not to be based there) and ensure Australian submarines can avoid its enormous shoal waters and deploy undetected from the deep water ports in the south to help protect the country.

That has been the essential model for a long time but some basic strategic facts have recently changed.

Sea lanes and shipping traffic through the Indian Ocean and the presence of gas and oil (click on the map below for details) in the country’s remote far northwest demand more attention be paid to the Indian Ocean, as opposed to the Pacific.

Already, Australia is deep into a series of major reviews. The new conservative government of Tony Abbott ordered another White Paper, a new Capability Plan and a workup on Defense Industry Capability. In plain English, that means a newish strategy, a plan for what Australia will buy and scrap and an analysis of whether the country has the labor, companies and technology to do what it wants to do. (The White Paper reportedly will justify almost doubling the Australian defense budget over the next 10 years to $50 billion from its current $25 billion. The Labour Party had promised the same figure, but only when circumstances allowed.)

So what are the big question these studies will need to answer?

First, who will be Australia’s best friends be and how close will the Aussies let them get? America will remain the foundation ally, but we are not likely to get everything we want from Australia. That’s not a base at Darwin, it’s more like a summer camp — except in winter. There’s lots of room to shoot and train in, but it’s nothing like a treaty base.

Britain still retains a unique relationship with Australia, thanks to the Commonwealth. That isn’t likely to change much. The most interesting shift may come in Asia. Australia has been under pressure from the United States to draw closer to Japan, with some talk of the two becoming allies. That is unlikely — in part because Japan did bomb Darwin and the memories of Japanese POW treatment are still pretty sharp here — but Australia has reasons to get closer to Japan. Australia needs new submarines, long-distance diesel submarines. America no longer builds diesel submarines. We’ve advised the Aussies that Japan makes the subs best-suited for their missions. As a first step, the two countries signed a defense technology sharing agreement on July 9. But just how far that cooperation will extend is, at this point, anyone’s guess.

The bill for those 12 or fewer submarines — between $20 billion and $36 billion will be enormous, especially by Australian standards. The prospect of buying submarines ready-made from another country is painful, as Australia is keen to preserve its defense industrial base. The company called ASC, based in Adelaide, is key to all this. Created when Australia bought the hugely expensive and long-troubled Collins-class submarines, the labor and technology ASC boasts after having assembled the Collin’s class boats will be key to the country’s choices. Much remains up in the air here.

The size and make-up of the Australian Army remains a huge unknown. Comprising almost half of the Aussies in uniform (58,000), the Army has the most questions to answer about its future. Aside from supplying most members of the the superb Special Air Services Regiment, the Army’s key missions are a bit of a puzzlement. Should most of the force be structured to repel invaders up north, as has been the case for many years? Should some of the force be structured to fight alongside the United States and other allies? If so, what kinds of wars are most likely? I understand the Australian military — small as it is — is judged well capable of defeating Indonesia, traditionally regarded as the most likely threat. What else should the Army be built for?

The other standout question for Australia is likely to be just how fast and how many F-35s will the country buy. I don’t doubt their commitment to buying the aircraft, but how many will they buy and when — once the initial 60 have been bought for more than $12.4 billion?

As the White Paper grinds its way through the policy sausage maker in Canberra, one strategic issue will shape much of what else comes: what is Australia’s relationship with China likely to be. Are the Chinese a competitor? Are they a key trading partner? How do we manage our relationship with the Americans and the rest of Asia as China’s economy and ambitions grow? Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s government may be pressing for a tougher stand on China than the last White Paper took, but the realities of Australia’s geography, population and economy place very real constraints on the Lucky Country.

australia gas and oil map

australia gas and oil mapIn World War II, this country served the allied cause as a giant aircraft carrier and port, providing planes, men and materiel to deploy throughout the Pacific. Allied aircraft flew from the northeastern town of Cairns during the Battle of the Coral Sea — known by some as the “battle that saved Australia.”

The Battle of Milne Bay on the eastern tip of New Guinea, little known to Americans, marked the first time allied troops turned back what had been the unstoppable Japanese. Australians fought that battle, aided by allied aircraft flying from an airstrip inland of the port of Townsville, which played crucial roles in virtually every battle of the Pacific.

Today, the strategic situation is very different. The greatest threats to peace in the region are North Korea and an increasingly assertive China. Indonesia has replaced Japan as the central threat faced by the Australia, although relations between the two states have improved considerably over the last two decades. Defense policymakers still consider the Aussie military’s ability to defeat Indonesia a primary benchmark.

What does all this translate into? Defend Australia from the north (hence the carefully circumscribed agreement to allow US Marines to operate from Darwin but not to be based there) and ensure Australian submarines can avoid its enormous shoal waters and deploy undetected from the deep water ports in the south to help protect the country.

That has been the essential model for a long time but some basic strategic facts have recently changed.

Sea lanes and shipping traffic through the Indian Ocean and the presence of gas and oil (click on the map below for details) in the country’s remote far northwest demand more attention be paid to the Indian Ocean, as opposed to the Pacific.

Already, Australia is deep into a series of major reviews. The new conservative government of Tony Abbott ordered another White Paper, a new Capability Plan and a workup on Defense Industry Capability. In plain English, that means a newish strategy, a plan for what Australia will buy and scrap and an analysis of whether the country has the labor, companies and technology to do what it wants to do. (The White Paper reportedly will justify almost doubling the Australian defense budget over the next 10 years to $50 billion from its current $25 billion. The Labour Party had promised the same figure, but only when circumstances allowed.)

So what are the big question these studies will need to answer?

First, who will be Australia’s best friends be and how close will the Aussies let them get? America will remain the foundation ally, but we are not likely to get everything we want from Australia. That’s not a base at Darwin, it’s more like a summer camp — except in winter. There’s lots of room to shoot and train in, but it’s nothing like a treaty base.

Britain still retains a unique relationship with Australia, thanks to the Commonwealth. That isn’t likely to change much. The most interesting shift may come in Asia. Australia has been under pressure from the United States to draw closer to Japan, with some talk of the two becoming allies. That is unlikely — in part because Japan did bomb Darwin and the memories of Japanese POW treatment are still pretty sharp here — but Australia has reasons to get closer to Japan. Australia needs new submarines, long-distance diesel submarines. America no longer builds diesel submarines. We’ve advised the Aussies that Japan makes the subs best-suited for their missions. As a first step, the two countries signed a defense technology sharing agreement on July 9. But just how far that cooperation will extend is, at this point, anyone’s guess.

The bill for those 12 or fewer submarines — between $20 billion and $36 billion will be enormous, especially by Australian standards. The prospect of buying submarines ready-made from another country is painful, as Australia is keen to preserve its defense industrial base. The company called ASC, based in Adelaide, is key to all this. Created when Australia bought the hugely expensive and long-troubled Collins-class submarines, the labor and technology ASC boasts after having assembled the Collin’s class boats will be key to the country’s choices. Much remains up in the air here.

The size and make-up of the Australian Army remains a huge unknown. Comprising almost half of the Aussies in uniform (58,000), the Army has the most questions to answer about its future. Aside from supplying most members of the the superb Special Air Services Regiment, the Army’s key missions are a bit of a puzzlement. Should most of the force be structured to repel invaders up north, as has been the case for many years? Should some of the force be structured to fight alongside the United States and other allies? If so, what kinds of wars are most likely? I understand the Australian military — small as it is — is judged well capable of defeating Indonesia, traditionally regarded as the most likely threat. What else should the Army be built for?

The other standout question for Australia is likely to be just how fast and how many F-35s will the country buy. I don’t doubt their commitment to buying the aircraft, but how many will they buy and when — once the initial 60 have been bought for more than $12.4 billion?

As the White Paper grinds its way through the policy sausage maker in Canberra, one strategic issue will shape much of what else comes: what is Australia’s relationship with China likely to be. Are the Chinese a competitor? Are they a key trading partner? How do we manage our relationship with the Americans and the rest of Asia as China’s economy and ambitions grow? Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s government may be pressing for a tougher stand on China than the last White Paper took, but the realities of Australia’s geography, population and economy place very real constraints on the Lucky Country.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar

Catatan: Hanya anggota dari blog ini yang dapat mengirim komentar.